Advertisement

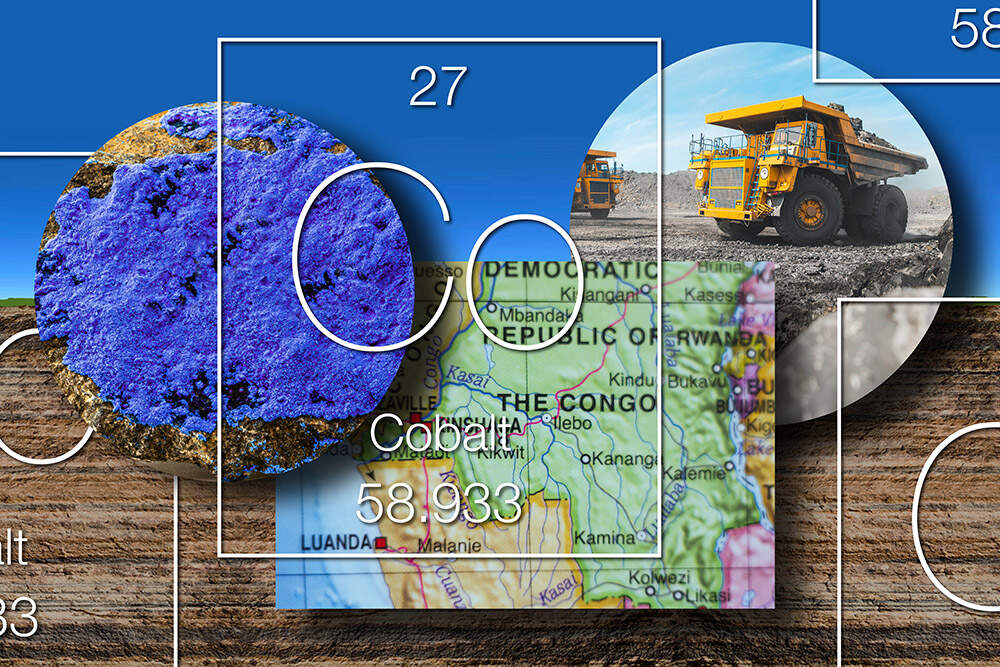

The human cost of cobalt: Modern slavery in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Resume

Most of the world’s cobalt is extracted in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

But to get it, hundreds of thousands of Congolese people labor with no other means to survive.

Today, On Point: Episode three of our special series discusses cobalt and the human cost of mining.

Guests

Siddharth Kara, associate professor of Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery at the University of Nottingham. Author of "Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives."

Also Featured

Annie Sinanduku Mwange, president of the National Network of Women in Mining (RENAFEM).

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, professor of African and Afro-American studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Permanent representative of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the United Nations since 2022.

Interpretation and translation by Adele Sire.

Transcript

Part I

PRES. JOE BIDEN: I've signed a historic piece of legislation here in the United States that includes the biggest, most important climate commitment we have ever made in the history of our country.

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: President Biden set the goal. Cut U.S. carbon emissions in half by 2030.

BIDEN: So let this be the moment we find within ourselves the will to unlock a resilient, sustainable economy to preserve our planet.

CHAKRABARTI: Achieving that goal will require vast amounts of lithium.

This lithium deposit is one of the richest ones in North America.

CHAKRABARTI: Copper.

STEVE KESLER: We are at probably an inflection point in the annual demand for copper.

CHAKRABARTI: Cobalt.

SIDDHARTH KARA: The only way to survive in that part of the Congo is to pick up a strip of rebar or their bare hands and start digging in pits for cobalt, because it's everywhere.

CHAKRABARTI: Nickel.

CHRISTOPHER POLLON: And if you're looking at a Ford F-150 Lightning, we're looking, I think, almost at about 180 pounds of just nickel in that battery.

CHAKRABARTI: Each element serves a different purpose, but they all have one important thing in common.

DOUG WICKS: Without mining, there will not be a clean energy transition.

CHAKRABARTI: But increasing mining to meet our clean energy needs comes at a cost.

AIMEE BOULANGER: If we're going to be using these materials, we need to first of all be honest with ourselves and be more aware.

CHRISTOPHER POLLON: Especially if you look at the environmental and social costs of becoming a smelting and mining and battery hub to the world.

FARRELL SMITH: It's not up to you to decide what to do with this land. This is their land.

This is their ancestral land, and they don't want this to happen.

CHAKRABARTI: I'm Meghna Chakrabarti, and this is an On Point special series.

DAVID ROBERTS: There is no math about the new demand for these minerals.

PROTESTOR: All the mining companies, they're billionaires, and we're still poor, destitute, struggling!

DAVID ROBERTS: The most negative story you could tell, the worst assumptions you could project.

PROTESTOR: To take the lithium out of this ground is another form of genocide, or cultural genocide.

DAVID ROBERTS: Still, it's going to be a vast improvement on the ongoing apocalypse that is the fossil fuel economy.

CHAKRABARTI: "Elements of energy: Mining for a green future." Episode three, the human cost of cobalt. We'll start with Ernest Scheyder and some quick facts about cobalt.

ERNEST SCHEYDER: Cobalt is a bluish metal that, when added to an electric vehicle battery, can help reduce rare yet spontaneous combustions known to scientists as thermal runaway. The Democratic Republic of the Congo holds the world's largest supplies of this key metal. And it's the largest producer. The use of child labor, in some instances, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to produce cobalt has become a large concern for automakers, regulators, and policy makers across the globe.

CHAKRABARTI: Quote, "We collect dirt. The kids help by packing it up and washing it. They also sort through it, looking for minerals.”

That is what a woman named Mama Natalie told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2022. They filmed her climbing an almost vertical multi-story embankment of red waste dirt, discarded by a Chinese owned mine in Southern Congo. She digs by hand, along with hundreds of other families. Her two small sons sort through the rocks looking for signs of the blue-green element. They carry their finds down the embankment in small cloth bags.

(MAMA NATALIE, CONGOLESE)

“I come to the mine to hustle,” Mama Natalie says. “If I’m lucky, I make some money and buy food for the kids. But if I don’t, they go to sleep hungry.”

70% of the world’s cobalt comes from Congo. The majority of that comes from large mining operations that are mostly Chinese-owned. But a third of it is hand dug by so-called “artisanal miners” like Mama Natalie. It is largely unregulated, extremely dangerous, and a last resort being taken by more than 255,000 artisanal miners, including 40,000 Congolese children.

The 103 million people of the Democratic Republic of the Congo live in one of the five poorest nations in the world, according to the UN. More than 60% of its people live on less than $2.15 a day. But they live in one of the world’s most resource-rich nations. The ground beneath their feet holds almost unimaginable value.

ANNIE SINANDUKU MWANGE (TRANSLATION): “In some places, the mines are right near the village, in which case you would walk 15 to 30 minutes to get there.”

CHAKRABARTI: Annie Sinanduku Mwange is president of the National Network of Women in Mining. There could be more than 3.5 million tons of cobalt in Congolese soil, according to a recent study by the business intelligence firm GlobalEdge. The untapped raw mineral deposits could be worth more than $24 trillion.

Mwange says none of that wealth goes to the miners.

MWANGE (TRANSLATION): It’s a real problem. Sometimes, miners go in without boots, goggles, gloves, or helmets, either men or women. They have no boots. They go barefoot or wear sandals. There are tools but not enough of them. You can buy them or give them to the mine managers but they don’t have the means to purchase those.

CHAKRABARTI: Mwange told us, the mines are also poisoning villages across Southern Congo.

MWANGE (TRANSLATION): When you extract the minerals, the waste is dumped in the environment where people live. In the river, the waste poisons the fish, and people who use this water can become ill. Children are born with birth defects.

But there are also several illnesses caused by the minerals because they work without safety protection. They may wade into polluted water, and there is a problem with tuberculosis, because they screen minerals with sieves and do not wear masks, so they inhale dust and this causes tuberculosis.

CHAKRABARTI: The Democratic Republic of the Congo has one of the most tragic histories of any nation on the African continent. It suffered brutal atrocities for almost a century under Belgian rule. After independence in 1960, the country was repeatedly shattered by secessionist movements, assassinations, and dictatorship. Beginning in 1996, two Congo wars killed almost six million people.

(SOUND OF ARTILLERY FIRE)

Currently, in Eastern Congo, more than 100 armed rebel groups, some with direct aid from neighboring Rwanda, are fighting for control of mineral-rich lands. The fighting has displaced more than a million people in just the first three months of this year alone.

This man demanded that the Congolese government do everything it can to stop the wars. He spoke to a Voice of America camera crew as thousands of displaced people walked slowly on the red dirt road behind him.

CONGOLESE MAN (TRANSLATION): “We need help. The population is tired of the ongoing wars,” he said. “The children are dying on the roads during the long walks.”

CHAKRABARTI: As war, corruption, and poverty continue to drain away opportunity and development in Congo, they are replaced by the world’s soaring need for cobalt. From 2000 on, demand for the element grew more than 25-fold in just two decades.

MWANGE (TRANSLATION): With minerals, there is cash. You can make money with this line of work, other jobs don’t pay as much.

CHAKRABARTI: Annie Sinanduku Mwange, president of the National Network of Women in Mining.

MWANGE (TRANSLATION): We began to notice that a lot of your young women were leaving the city to work in the mines. When they returned to the home, they had money, but after a while, they would get sick and die. We didn’t know what they were doing in the mines.

CHAKRABARTI: Mwange says women trying to scrape together money from mining are often forced to give sexual favors to access the mines, and many also end up in prostitution.

MWANGE (TRANSLATION): When we went over there, we saw for ourselves what was really happening. Women would be forced to have sex with the miners, and they would contract STDs.

CHAKRABARTI: Young girls have been raped. According to reporting from the New Yorker, miners sometimes believe that having sex with a virgin girl increases their luck in the mines.

In the United States, President Biden has called for the U.S. to make major strides forward in green energy, and cut its emissions in half by 2030. By that year, cobalt demand is expected to double from current levels.

Congolese men, women, and children will continue to go down the unregulated, unsafe mines.

Mama Nicole’s son did. Deomba was 13 years old when the mine he was in collapsed, burying Deomba and his friend alive.

“I was at church, and they called me and said, ‘Your child went into the mine and is now dead.’” she told Michael Davie in the Australian Broadcasting Corporation documentary “Blood Cobalt."

“I said no, my child never goes there,” Mama Nicole tells him.

CHAKRABARTI: They brought Deomba’s body back to her village. Mama Nicole could barely afford the small wooden cross for her son’s grave.

On their way to the burial, Mama Nicole and her family were stopped by the village leader.

VILLAGE LEADER: “Mama?”

“The chief is coming.”

CHAKRABARTI: He wouldn’t let them pass without payment.

The Australian journalists paid the bribe. Only then could Mama Nicole lay her son to rest.

(MAMA NICOLE WAILS)

CHAKRABARTI: When we come back --

SIDDHARTH KARA: Companies at the top of the chain – big tech and EV companies – will say, we buy cobalt from A, B, C mining company, and there’s no child labor or artisanal labor. And the assumption is, who’s going to get down there and demonstrate otherwise?”

CHAKRABARTI: Congo, and the human cost of cobalt continues in our series, “Elements of energy,” in just a moment.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: I'm Meghna Chakrabarti, and you're back with On Point's special series Elements of energy: Mining for a green future. And today, in episode three, the human cost of cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. And we're joined now by Siddharth Kara. He's author of "Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives."

Siddharth, welcome to On Point.

SIDDHARTH KARA: Hi, thank you Meghna.

CHAKRABARTI: So first of all, let's get a deeper understanding of how important cobalt is for a clean energy transition. We mentioned briefly earlier that it's a critical element to stop that so called thermal runaway or batteries from setting themselves on fire.

Tell us more about why we need so cobalt.

KARA: Cobalt is an essential component to almost every rechargeable battery made today, because it does two very important things. No. 1, it allows that battery to hold maximum energy density and remain thermally stable through repeated charge and discharge cycle. So what does that really mean? It means that you and I don't have to plug in our smartphone as often. Or if we have an electric vehicle that car can drive further without having to plug it in to recharge it.

CHAKRABARTI: So Congo contains, in terms of the world's cobalt reserves, about half the world's reserves, but 70% of the cobalt that's being put into global markets now comes from that one country.

I would love for us to understand the various major players that have led to the terrible exploitation that's going on in Congo to get this mineral or this element out of the ground. There are three or four key elements or groups as far as I can see. China, which we'll talk about. Major tech and battery development companies, and the international community, including the United States.

Plus, the Congolese government. So let's begin with China. How would you describe China's control of the cobalt in Congo?

KARA: China dominates cobalt production in the DR Congo. They saw the future. Years and years before Western nations did, they saw the future was going to be a rechargeable economy and this transition to sustainable energy, it would require cobalt.

All that cobalt is in the Congo. And beginning in 2009, they started signing deals, aid and infrastructure deals in exchange for access to mining concessions. And they probably control about 70% to 80% of Congo's cobalt mining production today. They have vertically integrated that supply chain from dirt to battery.

So most of the Congo's cobalt is produced by Chinese state-run mining companies. It then flows to China for commercial grade refining, and then to battery manufacturers and into the devices and cars you and I use every day.

CHAKRABARTI: And of course, we could put the mirror on ourselves right now in the United States and the international community and say, "Oh this has been going on," like you said, "since 2009." But it's only in recent years that it's become more of an open issue or the awareness has grown in Europe and the United States. Because, oh, look, we need that cobalt too for our own desires for a clean energy transition.

The thing that I find very ironic, Siddharth, is that then Congolese President Joseph Kabila opened the door to China's involvement in Congo because he had a plan to rebuild the country's domestic Infrastructure, to pull Congo out of poverty, right? This plan was titled Les Cinq Chantiers, right?

Or five public works. Can you tell us a little bit more about what Kabila had hoped for in giving China such favorable contracts to control so much of the cobalt?

KARA: You're right. The aspiration was this exchange that, okay, we have all these enormous resources that are needed for the future's rechargeable economy.

China has capital and mining expertise. So we'll give you access to those resources in exchange for, of course, some money. And then infrastructure projects, please build the thousands of kilometers of roads that we need, expand electrification sanitation construction projects.

That was, at least on paper, that was the aspiration, but of course it hasn't been realized. China has gained access to this enormously valuable mineral. But when you're on the ground in the Congo, and I've spent months there on the ground, the construction projects are years and years behind schedule.

The work is done in a shoddy manner. And very crucially, Meghna, it didn't lead to employment of Congolese people, which is desperately needed. You touched in your opening segment, the grinding poverty of that country. Chinese construction companies imported Chinese laborers to do all the work.

And then ship them back. So it really has not yielded the hopes and aspirations and benefit for the Congolese people. It's essentially resulted in this pillage of the Congo's resources that has just been siphoned out and fed up this supply chains into our gadgets and cars.

CHAKRABARTI: To be clear, Siddharth, when you say do all the work, do you mean the mining or the running of the mines, the running of the processing facilities, the middlemen who are buying the raw ore from miners and then selling it to Chinese companies?

Can you clarify?

KARA: Yeah, so they're at the bottom end of what we'd call the formal economy, and into the informal economy. So they're the nexus point between artisanal miners and the formal supply chain through these trading networks, these depots and buying houses that buy the production of artisanal miners.

And then they also are the laborers doing the construction projects that were supposed to be done by Congolese citizens. And then of course they're running the mining companies that China has in the Congo.

CHAKRABARTI: I see. So the infrastructure construction projects is what you were talking about.

Thank you for that clarification.

KARA: Yes, of course.

CHAKRABARTI: But long story short, Congo's hopes for a vastly improved system of education, health care, employment, water, electricity. All of that, 15 years later, has not yet come to pass.

KARA: Oh, not a modicum of it. Everything is only getting worse for the people of the Congo.

It's on the ground, you see it. And some of the people in your first segment talked about it. They have not benefited. And historically, the people of the Congo have never benefited from these rich resources, which with the country has been both blessed and cursed.

CHAKRABARTI: So just a couple more quick questions about China's role here. Because it raises so many issues and questions for how Europe and the United States, and we'll focus on the U.S. in particular, is going to handle managing its increasing need for cobalt because of the obvious geopolitical tensions already in existence between the United States and China.

But I wonder, as you well know, Siddharth, it was only a couple of years ago that it was revealed how wildly corrupt President Kabila was. In those initial agreements, that his government signed with China and the Chinese companies that came into Congo. Is there any evidence that what Kabila had promised the Congolese people was ever going to be even possible, or was it baked in the cake with those agreements that China was just going to get the cobalt that it wanted with very little in return?

KARA: I think that's right. There's been a good bit of journalism on this now and investigations. Kabila pocketed a substantial amount of money in exchange for signing these deals. It was essentially bribe money and kickbacks to the tunes of tens of millions of dollars, maybe even hundreds of millions of dollars.

And that's also been a part of the problem is the poor governance that has been such a problem for the Congo since independence, one kleptocratic leader after another taking their share of the country's wealth, in exchange for looking the other way while foreign powers come in and pillage the country's resources.

CHAKRABARTI: One lesson coming out of this. It seems to me that almost every single group that has any leverage over bettering the lives of the people of Congo are not using that leverage. Because that brings us to the next big player in this situation, in this system that's evolved, and that is the very companies, battery makers, tech companies, et cetera, trillion-dollar companies that are buying the cobalt.

How would you describe their role here?

KARA: Demand this scramble for cobalt. Okay. This enormous scramble that has unleashed so much violence and suffering on the people and environment on the Congo. That demand starts at the top of the chain. That's tech companies and car manufacturers making electric vehicles. And everything that's happening downstream from there is a consequence of that enormous scramble, that demand that has been magnified by Western policy mandates to escalate this transition, especially from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles.

And nothing inherently wrong with that. It's probably a good thing in the long term, but no one stopped to see as we charge forward with this transition, are we trampling on anyone along the way? And in fact, that's exactly what's happened, is the global economic order has its foot on the neck of the Congolese people.

And it's saying dig. And that's an injustice. And that has to be set right. So everything that's happening, all the corruption, all the violence, all the bad actors, it's all a consequence of this scramble that's been ignited by Chinese and Western governments pushing these policies.

CHAKRABARTI: Siddharth, can you just repeat that last sentence that you said? Because we just lost you for just a second or two.

KARA: This scramble, this scramble that's been created, this fever is a function of tech companies and EV companies demanding cobalt and the policy mandates by Western countries that have escalated this transition. And no one stopped to see, are we trampling on people as we make this transition, and in fact we are trampling on the people in the heart of Africa.

CHAKRABARTI: So here's the thing that perplexes me, Siddharth, because first and foremost, it is so well documented how much exploitation is going on in Congo. With the miners. We talked about child labor, we talked about, completely impoverished families digging through waste piles of dirt to find just scant amounts of cobalt so that they can eat dinner that night.

There's the illegal mines that the artisanal miners are building, which have no supports in them whatsoever. But since cobalt is everywhere there's no reason for the miners to stop trying to find it. And then in addition, there have been formal human rights reports that have documented all of these facts about Congo on the ground.

The portions of documentaries that we used in the top of the show, they're right there on YouTube. People can see what the conditions are right now. So why is this going on? When, for example, when exploitative conditions were found in Chinese factories, Apple stepped in and said, Nope, we're going to do everything we can to increase the quality of work and the human rights of those workers in our factories.

But they're not doing the same in Congo?

KARA: No, no one is. And there's a short answer. And then there's a longer answer. The short answer is no one is taking responsibility for what's happening at the bottom of global cobalt supply chains. Because it's African people in grinding poverty and it's full stop.

That's the short answer. And that's been the answer about the relationship between the global north and the continent of Africa going back centuries. This is just the latest chapter in a long history of pillage that you touched on in your opening segment vis-a-vis the Belgians, Leopold and all the way back to the slave trade.

No, they don't count the same. They've never counted the same as you and I. Now, the more nuanced explanation is everybody, meaning tech companies and EV companies, when you show them this evidence from the ground, when Congolese people speak their truth, they'll all say it must be in someone else's supply chain.

It's not in my supply chain. My supply chain is audited. And then they all say this. And of course, if that's true of everyone, then where's all this cobalt going? To the tunes of hundreds of thousands of tons dug by hand by Congolese people every year. Where's it all going if it's not in any of their supply chains?

And that's working to a point, but eventually the companies at the top of the chain will have to accept responsibility for the conditions at the bottom of their chain. And treat the people in the Congo with the same respect and dignity as they would treat their own employees at headquarters.

CHAKRABARTI: Will they? Just this month, a U.S. Court of Appeals absolved Apple, Alphabet, Dell, Microsoft, and Tesla from any responsibility in the harm suffered by the Congolese people. They said, the appeals court said that those companies did not have anything more than an ordinary buyer-seller transaction with suppliers in the DRC, so they're not legally liable for supporting child labor.

KARA: I think we have to go past the idea of strategic litigation and making legal arguments and appeal to the moral and ethical imperative of ensuring that when you say your supply chain is untainted by child labor, or forced labor, or hazardous labor, or degrading labor, or environmental destruction, that you actually put boots on the ground and make sure that's true, rather than just have your marketing teams put out statements saying that this is what's happening.

And the more that truth seekers go down into the Congo and bring the truth of this horror out into the world, we'll reach that inevitable tipping point, as has always been the case with advancements in human rights and social change. We'll reach that tipping point where people with moral rigor will demand that these injustices be set right, and they won't stop until they drag humanity and these companies forward in doing it.

That's how the first Congo horror was addressed and resolved. It started with the explosion of awareness about the horror pushback from Leopold saying it's not my responsibility. Or it's not as bad as people are saying. And eventually champions emerged, and awareness reached a tipping point, and justice was done.

CHAKRABARTI: We're going to talk a little bit more about that history later in the show. And also, I have some questions about the role of the Congolese government itself here. But Siddharth, in the interim, what's stopping more cobalt from being mined from reserves outside of Congo? Where potentially there could be greater regulation and a moral grounding, if I can put it that way, of that cobalt coming out of the ground.

KARA: There are cobalt reserves scattered around the world, of course, but at least half is in a small patch of the Congo. So you can't get around Congo, in terms of all the forecasts for future demand. The other issue is it's not just a function of there's so many tons of cobalt in this country, in that country, the Congo's cobalt is also very high grade.

That means, basically, it's purer than most cobalt reserves in other parts of the world. So yes, we should mine cobalt in North America and Australia. In Europe. Wherever reserves are found. But that doesn't mean we just turn our backs on what's happening in the Congo. In fact, that has to be addressed to make this transition ethical and moral and decent.

We have to address this enormous violence that's been unleashed on the people of the Congo and the destruction of their environment just to save our own.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: I’m Meghna Chakrabarti. You’re back with On Point’s third episode in our special series “Elements of energy: Mining for a green future.” Today, it’s the human cost of cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

We’re joined by Siddharth Kara. He’s the author of "Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives."

Now, as we mentioned, resource extraction and exploitation have long been part of Congo’s history. Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja is the Permanent Representative of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the United Nations.

He says we must first look back to the mid-19th century, and Belgium’s King Leopold II.

GEORGES NZONGOLA-NTALAJA: In the 1840s, he heard about the Congo and how rich it is. And so he hired a journalist, Henry Stanley. Who wrote a lot of things about the Congo, to be his agent in the Congo. And Stanley went and had some 400 treaties signed with African rulers.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, most of the rulers could not read. So Stanley lied to them, claiming the treaties stated that King Leopold would help the Congo become a modern place.

NZONGOLA-NTALAJA: The reality said that I, King so and so, give away my land to King Leopold II of the Belgians. And that's how King Leopold succeeded in convincing the other European powers and the United States to recognize Leopold's claims to the Congo.

CHAKRABARTI: Those Major European powers negotiated and formalized claims to territory in Africa at the Berlin Conference of 1884. And they recognized King Leopold as the sovereign of the Congo Free State. So-called Congo Free State. He ruled over a land rich with ivory, palm oil, and rubber. Which would become invaluable just a few years later with the advent of the modern “vehicle powered by a gas engine."

Yes. Meaning cars. Which meant tires. Which meant money.

NZONGOLA-NTALAJA: The King required that his administrators send him all the quantities of rubber he wanted, and that meant that is necessary for all villages who are in areas where rubber was found, bring said quantities of rubber each day, and if they did not bring the required quantity, sometimes they would cut their hands.

CHAKRABARTI: It is true. Rubber for internal combustion engine automobiles in the 19th century, cobalt for electric vehicles today. But back then, Leopold ruled with systematic brutality. Forced labor, torture, murder, kidnapping, and as Professor Nzongola-Ntalaja says, amputating the hands of men, women, and children when rubber quotas were not met.

As many as 10 million Congolese died under Leopold’s rule. And in 1908, international pressure forced Leopold to turn the Congo Free State over to Belgium. However, they simply picked up where Leopold had left off.

NZONGOLA-NTALAJA: The system of forced labor continued. And also because Congo is very rich in mineral resources. They sent people from their villages to a place far away to work on the mines and the railroad and on many other things.

CHAKRABARTI: A rapidly industrializing world had an insatiable appetite for the minerals in Congo’s soil. For example, when the U.S. built its first atomic bomb in the 1940s, its key component – uranium – was extracted from Congo.

NZONGOLA-NTALAJA: We're looking at a similar situation today. Because we are so endowed in minerals that most of the major countries in the world, from China to the United States to Western Europe, they're all interested in getting these strategic minerals from the Congo, and this is one of the problems creating the war.

CHAKRABARTI: Professor Nzongola-Ntalaja is speaking of the ongoing violence committed by dozens of Congolese rebel groups fighting for control of Eastern Congo’s mineral rich lands. Since 1996, those militants have killed almost six million of their own people. That's the most or highest number of deaths since the second world war. Just as many have been internally displaced. In late 2022, a United Nations panel said it found “substantial evidence” of the Rwandan government supporting several of those armed groups.

Those findings haven’t stopped the European Union from partnering with Rwanda for these minerals. Despite calls from international human rights advocates, who say those minerals from Rwanda are illegally obtained from Congo.

NZONGOLA-NTALAJA: I served the Congo for 20 months as the ambassador of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the United Nations in New York, and I made plea after plea for the international community to impose sanctions on Rwanda. Nothing happened. It tells you something about how racism is still a phenomenon. And the question of the way our countries are treated by the developed countries of the West.

CHAKRABARTI: Thats Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja. He’s the Permanent Representative of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the United Nations, and professor of African studies at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

Siddharth, as you well know, and the professor there stated, the weight of Congo's colonial history and the violence met upon that country, is still profound and reverberates through the lives of Congolese people today.

That is, we must acknowledge that. I also do want to ask, though, how much shall we hold to account various leaders of Congo since its independence in 1960? We have 60 years now of Congo being a sovereign nation. And yet, as we've talked about, we've gone from war to war.

Dictatorship, corruption, and now an inability to stop the ongoing militant violence in eastern Congo. How much can the international community actually do when the governance within Congo itself seems hapless, to put it charitably?

KARA: Let's acknowledge two important things, Meghna. First, as you said, people in the Congo today are the inheritors of multiple generations of torment and violence and pillage.

They're born into that multi-generational pain, and you feel it on the ground. You see it in people's faces as they eke out this base existence, continue to eke out this base existence at the bottom end of the global economy. But yeah, what is the role of the Congolese government? I think it's an interesting question and it's a very important post-colonial question.

60 years of freedom is not that long, right? It's a new country, but it was born, and it attained independence in the midst of violence and ongoing colonial interference. If when you talk to Congolese people about this question, as I have of poor governance, they say, look, we tried to have good leadership.

We elected Patrice Lumumba as our first prime minister. And he promised that he would use Congo's resources for the benefit of Congolese people. That was his bold, anti-colonial nationalist vision for a free Congo. And within months, he was dispatched and assassinated by Belgian and neocolonial Western powers.

And in his place, propped up a bloody, corrupt dictator, Joseph Mobutu, who ran the country into the ground, but continued the flow of Congo's valuable resources, especially its minerals to Western countries. So Congolese people will say, you taught us the lesson within months of independence of what happens if we try to stake our own path.

And so since then, it's been leader after leader, just playing ball with the Western agenda.

CHAKRABARTI: Point well taken. So then tell me how you see some of the activities that happened in the past couple of years, like in 2019, the democratic Republic of the Congo created, L'Entreprise Générale du Cobalt, right?

It's a state-owned mining company that's supposed to have a monopoly or control over all that artisanal mining that we talked about before and this was created in 2019. But just last month, the CEO said that artisanal cobalt monopoly could launch within a couple of months.

First of all, how would that work?

KARA: Yeah, so there's a very funny thing that happens at the bottom of the global economy. And it's this sort of, this contest of storytelling and there's a certain story that's told outside of the global South, in this case, outside of the Congo about what's going to happen on the ground.

Okay. No, there won't be children working in so and such mine. Oh, we'll create an entity to pay good prices for artisanal cobalt. And then you get on the ground, and you realize that none of it is really achieved or achieved in the way it's described. It's used as a misdirection or a smokescreen to do what?

To persuade you and I to just keep consuming, to not worry about it. And that state run buying agency has neither the budget or the capacity to actually pay reasonable prices to artisanal miners, who are still, would still nonetheless be digging cobalt out of the ground in toxic conditions, rinsing it and sorting it in toxic conditions without personal protective equipment, children won't be suddenly going to school.

They'll still be working alongside their mothers and fathers. So it's part of this sort of narrative or building a narrative that just look the other way. Everything's being dealt with. Everything's being sorted. We have solutions, but the truth, as you showed in your segment, and as people can hear and see on YouTube or read my book. The truth is being spoken by the people of the Congo.

They continue to be, to dig for cobalt in highly hazardous, dangerous, subhuman and degrading conditions. And let's not forget also the enormous environmental contamination and destruction that's been caused by this scramble for cobalt. I wonder, then, if there are other places to look, to apply pressure.

We talked about China's control basically of the cobalt that's being pulled out of the ground and processed from Congo. Could the international community apply some pressure there? I think it is two very powerful levers that could be pulled. No. 1, the ultimate endpoint of this cobalt, which is the tech and EV companies, they should have teams on the ground. Rather than just pointing the finger downstream as saying it's the responsibility of the mining company.

It's the responsibility of the Congolese government. Ultimately all that cobalt ends up in the products they're selling to you and I. And it comes with assurances that human rights standards and norms and dignity are preserved and protected, but none of them have feet on the ground to actually make sure that's the case.

So if they suddenly said, "Look, we're not going to buy anybody's cobalt until we independently can be assured that the conditions under which it's mined meet international human rights standards," things might start to change. Every time, also, every time a Western government passes a policy and says, "Okay, by 2030, no more gas-powered cars can be sold in this country or this place."

In the same breath, you have to say, we're also allocating resources to make sure that doesn't lead to this cascading eruption of violence and suffering for the places where those component metals required for this transition are being mined We've charged forward without doing the work of making sure that we're mitigating and addressing the enormous violence and human rights violence that's taking place as a result of these policies.

CHAKRABARTI: As I mentioned before, the United States is becoming much more interested in what's happening in cobalt. Because we need, sorry, what's happening in Congo. Because we need the cobalt. Just, what, last year USAID launched a $20 million program to give grants to U.S. companies and mining entities that are interested in sourcing minerals from Congo if they agree to integrate local companies into that supply chain and protect artisanal miners who are mining the cobalt.

And there's been some other activity here. I'm looking in the Wall Street Journal. And USAID, their reporting said that it's going to also work more directly with companies on the ground in Congo. The labor department says it's working with officials in Congo to improve working conditions and oversight.

Does this give you any faith or confidence that increased U.S. involvement could do anything to better the situation for the Congolese people?

KARA: It's not going to hurt. But part of the problem is there aren't any major U.S. mining companies operating in Congo. It's all China.

It's China plus one or two European companies. And unless you're at the bottom of the chain, you can't fix the problems at the bottom of the chain. And that's part of the problem. So yeah, maybe a few million here or there from USAID will help some communities. But ultimately, the big tech and EV companies that are swimming in profits, generated through the extraction of battery metals, especially cobalt in the Congo, need to allocate some of those resources and some of their capacity and expertise to getting on the ground.

It's not complicated, Meghna. It's much more complicated to design a smartphone or a car than it is to pay people a decent wage in the Congo and give them some boots and gloves.

CHAKRABARTI: So Siddharth, we have less than a minute to go. And since you mentioned phones, I have to say, in researching this show, I have not been able to look at my phone the same way ever since.

And most people listening to this right now will have a mobile device very close to them. What would you say to just everyday average folks? Can they make a difference in the situation for the Congolese people?

KARA: Absolutely. We should all feel outraged that we've been made unwitting participants in an invasion of the human rights of the people of the Congo by tech companies that have not seen fit to ensure that those people are treated with respect.

And every time that company markets to us, Oh, upgrade your phone. There's a new camera and a new this. You have to make a personal choice. Am I going to contribute to more demand-side pressure on this scramble and violence against the Congolese people? And that's a personal decision we must all make.

And we have to clamor, clamor for change on behalf of the people in the Congo and in concert with the people of the Congo. Clamor for dignity and justice for those people on the ground.

This program aired on March 13, 2024.