Advertisement

Immigrants came to this small Wisconsin city. So did the political rhetoric.

A Wisconsin city became a political flashpoint in the national immigration debate.

In On Point's latest collaboration with ProPublica: How Whitewater, Wisconsin has responded to a new wave of immigration.

Guest

Melissa Sanchez, reporter covering immigration and labor for ProPublica. Author of “What Happened in Whitewater."

Also Featured

Dan Meyer, police chief, Whitewater, WI.

John Weidl, city manager, Whitewater, WI.

Chuck Mills, owner, Mills Automotive, Whitewater, WI.

Ariel, resident of Whitewater, WI.

Karla Ruelas, bilingual legal crime victim advocate, New Beginnings, Walworth County, WI.

Juana Barajas, owner of La Tienda Mexicana San Jose, Whitewater, WI.

Transcript

Part I

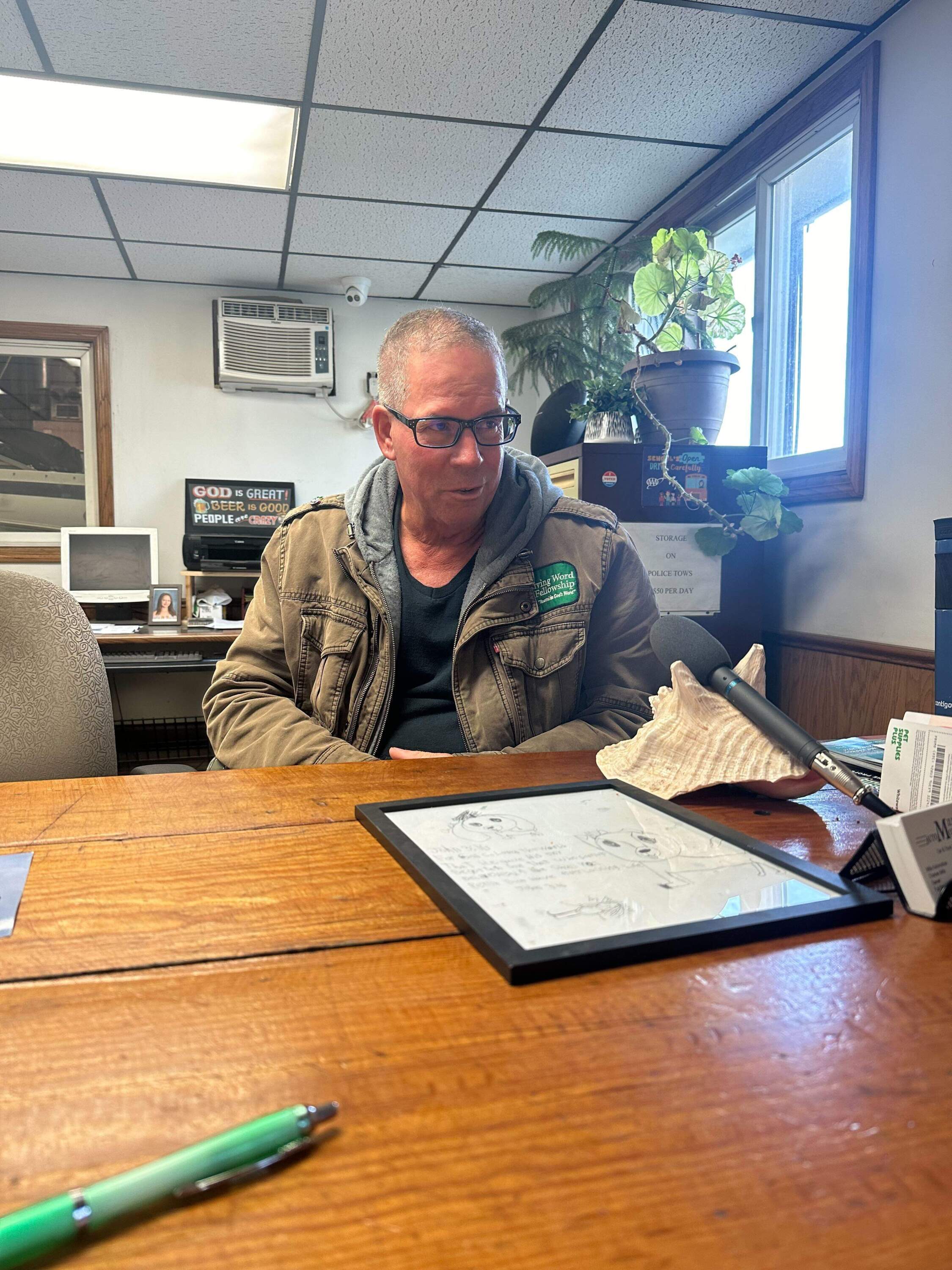

MEGHNA CHAKRABARTI: It's just after nine o'clock on a clear and crisp autumn morning. Chuck Mills has pulled into the gravel parking lot outside Mills Automotive, his towing and maintenance shop in Whitewater, Wisconsin. Two dogs hop out from his tow truck's cab with him. One sprints across the street to a nearby yard. The other dog trots up to two reporters, who also just pulled into the lot.

Me, and On Point Senior Editor, Dorey Scheimer.

We pass the dog's sniff test. And that's what probably helped us pass Chuck's test, too. He gestures to us to come inside.

The first thing I notice is a sign on the wall behind Chuck's right shoulder. It reads, God is great. Beer is good. People are crazy.

CHUCK MILLS: Faith just gives you a conscience. And my church is the best church.

CHAKRABARTI: Chuck is also resourceful. I'd forgotten the microphone stand in the car, so he pulls a large decorative conch shell to the middle of his desk.

Advertisement

The shell's pink spikes cradle the mic perfectly.

CHAKRABARTI [TAPE]: So we should be recording now.

MILLS [TAPE]: Okay.

CHAKRABARTI: And then, this resourceful and welcoming man begins to tell us the story of how, a few years ago, he was anything but welcoming when large numbers of Central American migrants began moving into his city.

MILLS [TAPE]: I was leading the crowd. They're going to turn us into a sanctuary city. You got to stop this. I screamed as far right as I possibly could.

CHAKRABARTI: This is On Point. I'm Meghna Chakrabarti. Welcome to the latest episode in our special collaboration with ProPublica, the independent nonprofit newsroom.

Whitewater, Wisconsin is about an hour west of Milwaukee.

The city of 15,000 is best known as the home of the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. But Whitewater is also surrounded by factories, food processing plants, and industrial agriculture. Employers in need of labor. In the aftermath of 2020, the town had housing, too, some left unoccupied by students during the COVID pandemic.

Whitewater Police Chief Dan Meyer says that's part of what drew a new wave of mostly Nicaraguan migrants to Whitewater. Estimates range from the hundreds up to a thousand, according to the Whitewater Police Department. And it's a change that some, including city officials, say has strained Whitewater's municipal resources, such as social supports, schools, and particularly law enforcement.

DAN MEYER: The amount of contacts we're having for operating without a license, that's tripled.

CHAKRABARTI: This is Whitewater Police Chief Dan Meyer. In December 2023, he wrote a letter to President Joe Biden and a dozen other federal and state officials, asking the government to fund new resources the city needed to cope with the recent influx of immigrants.

MEYER: It was a necessary intermediate step rather than just saying, hey, citizens of Whitewater, we're going to ask you to consider a referendum, knowing that this is an issue that goes far beyond the borders of the city.

CHAKRABARTI: The letter got picked up by right wing media, and inevitably --

DONALD TRUMP: Whitewater. Whitewater?

CHAKRABARTI: Donald Trump campaigning in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, last month.

TRUMP: Diseases are spreading like wildfire, all sorts of disease. The police say they cannot handle the surge in crime, the schools can't teach. And they're taking over the schools. The town's in big trouble.

CHAKRABARTI: ProPublica reporters Melissa Sanchez and Maryam Jameel spent six months reporting on Whitewater.

On Point also visited recently.

We all found that none of what Trump says is true. What is true is that Whitewater is changing. So we wanted to know. What does the city need now to serve all its residents, old and new?

MILLS: My name is Chuck Mills, and I've been in business here for 25 years. We're almost ready for retirement here, so that's one of the reasons I can speak out like I am.

CHAKRABARTI: Chuck was born and raised in Detroit. He and his wife started their family in Milwaukee. They moved to Whitewater when, in Chuck's words, their Milwaukee neighborhood got rough.

MILLS: So we came to find a place to raise our kids with a decent school system, safe place to live. The motive for coming out here was just to get my children in a good atmosphere to raise my children, and it worked.

CHAKRABARTI: It worked so well, Chuck wanted it to stay that way. That's why he had been one of the louder voices opposing the arrival of the new immigrants.

MILLS: Uncle Joe put out the invitation to everyone in the whole world to come on in, and it came really rapidly at the beginning. We didn't know how to deal with it.

Nobody did. This was all new to us.

ARIEL [TRANSLATION]: I left around 8:00 a.m. on a Thursday and arrived on a Saturday. I remember passing by Milwaukee, Dallas, Chicago. I was paying attention to the names of the towns that we passed.

CHAKRABARTI: Ariel arrived in Whitewater in 2020. He told his story to ProPublica's Melissa Sanchez. Ariel is from Murra, Nicaragua. He first entered the U.S. in 2019, seeking asylum. He spent four months in a Texas detention center, and he says he paid a $12,000 bond to get out. A nephew already in Wisconsin bought Ariel a bus ticket and helped him find his first job on a dairy farm.

Then, he landed in Whitewater, where food processing companies were hiring essential workers during the pandemic.

ARIEL [TRANSLATION]: Here, I could earn $100 in a day. Back home in Nicaragua, you maybe earn $50 in two weeks of work.

CHAKRABARTI: Ariel's dream was to bring his wife Maricela and their son to Whitewater, too.

ARIEL [TRANSLATION]: I told my wife, let me try, and then I'll see about bringing her so she can come with me. In reality, that's how it was. When I came, it was Donald Trump, and when she came, it was Joe Biden.

It was easier because there was more support for immigrants.

CHAKRABARTI: Ariel had a job, went to church, and had met a major milestone, settling his family in Whitewater. But he still faced a major obstacle. To get anywhere, work, school, the store, Ariel needed to drive. And he didn't have a license. In Wisconsin, unauthorized immigrants can't get a driver's license.

Asylum seekers like Ariel can, but the paperwork and testing requirements can still be a barrier. Chuck Mills says he saw the effects of that every day.

MILLS: They literally didn't know how to drive. They'd drive the wrong way up the one-way street. Run stop signs, this and that. Never fast. But at the beginning, we were scared. We were like, oh they're going to come up on the sidewalk and run our children over.

CHAKRABARTI: Ariel was one of those drivers.

ARIEL [TRANSLATION]: I always knew I was driving without a license. I was afraid of getting pulled over.

They've pulled me over seven times.

CHAKRABARTI: He feels that Whitewater police often unfairly pulled over immigrants.

ARIEL [TRANSLATION]: The other day I went to go pick up some mail where I used to live, some immigration paperwork. And I get there, I talk to the man there, and then I turned around, and there's the police. It's like he followed me.

He pulled me over close to the house. I hadn't done anything wrong.

CHAKRABARTI: Ariel got his first ticket for driving without a license in January 2022. In October that year, he was arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol after he drove into a ditch. He took his arrest seriously and didn't drive under the influence again. A few weeks after Ariel stopped driving, he, Maricela, and their son were dropped off near their home after a quinceañera party.

Maricela was crossing the street to their apartment when she was struck by a car driven by a former University of Wisconsin-Whitewater student. She died the next day. As far as we know, Chuck Mills and Ariel have never met. But their stories intertwine in the way lives do in a small community. Even Chuck knows about Ariel's loss.

MILLS: One Nicaraguan woman get run over in the dark with no bright clothes on, and so that's a tragedy.

CHAKRABARTI: Migrants who are caught driving without a license sometimes have their vehicles seized by police. And remember, Chuck Mills owns a towing company. So he was the guy police often called to tow the cars away.

MILLS: We tow it down here, of course they can have it right back next day, when they bail it out. So I'm dealing with all this. And by the way, I've never had a bad experience. Everybody's very humble, pay their bill, smile, thank us. Because even if you have the family car towed, it's better, still better than where they came from.

CHAKRABARTI: It's experiences like that which turned Chuck Mills into a supporter of Whitewater's immigrant community.

MILLS: No one's fighting, no one's arguing, no one's disrespecting anybody. We all shop at Walmart. We're getting along, we're neighbors.

CHAKRABARTI: In fact, the way Chuck talks, it feels like he has more shared values with the new migrant families than he did with the university students who once lived on his street.

Chuck's real beef is with the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, and how the town had become, by his lights, too dependent on that one institution for jobs and business. So he's thrilled that migrants are helping invigorate Whitewater's economy.

MILLS: Since the Nicaraguans got here, we've had a grocery store open up down the street here, and they're also liked by the community.

I shop there myself now and then, different things. And then there's a taco truck that shows up around Thursday that stays through Sunday. And the parking, it's like a zoo down there. You can't get in and out of the parking lot all day. And so they are a success story.

CHAKRABARTI: Chuck seemed at turns pensive about his changing community, then delighted by it.

But then, and most pointedly, frustrated by what he says is a federal narrative that's misrepresenting Whitewater and its Central American communities' real successes and struggles as they slowly adapt to each other.

MILLS: But in that evolving process, they found jobs. They got cars, they're driving to work, and they're raising their families, and they're just like you and I.

And we're all getting along and everybody's safe.

CHAKRABARTI [TAPE]: Can I ask you a question, Mr. Mills? At the beginning you said you moved to Whitewater for your family's well-being and safety.

MILLS [TAPE]: It's the same reasons they're here.

CHAKRABARTI: It's the same reason Ariel stays in Whitewater, without his wife, raising his seven-year-old son by himself.

And he echoes Chuck's frustrations with how the city has been represented, including by former President Trump.

ARIEL [TRANSLATION]: They take advantage of the subject and of the place because they know there's a lot of people who have come to Whitewater and who provide labor for this same country. But he doesn't know who is producing the goods.

For five years I've been living here. And for me, it's been a peaceful place to live and to work.

CHAKRABARTI: How long can that peace last? The next leader of the United States could have a radically different view on migrants everywhere, including Whitewater. So as we wrapped up our hour-long conversation with Chuck, I asked him one last question, and senior editor Dorey Scheimer followed up.

CHAKRABARTI [TAPE]: Do you mind if I ask if you know who you're going to vote for in the presidential election?

MILLS [TAPE]: You know it's President Trump. I'm very conservative, and not shy about it, but I'm also fair.

DOREY SCHEIMER [TAPE]: Can I just follow up, because President Trump has said on the trail that he has a plan to deport about 13 million people.

Would that be a big loss to this town?

MILLS [TAPE]: It's never going to happen. He's got to say what people want to hear. So that they'll vote for him, once he's in there. He's going to do the same job he always did. He didn't go after the Hispanic population or any immigrant population last time. He only went after MS-13. He only went after murderers and rapists, and he didn't go after anybody. And I doubt if he's gonna go after anybody this time. It's not gonna happen.

Part II

CHAKRABARTI: You're back with On Point. I'm Meghna Chakrabarti, and this is another special episode in our collaboration with ProPublica. And today we're talking about Whitewater, Wisconsin, and what a community needs to serve all of its residents when a large number of new migrants are arriving. And joining us now is Melissa Sanchez.

She is a ProPublica reporter who covers immigration and labor. And she and Maryam Jameel co-reported the story, What Happened in Whitewater. Melissa, welcome to On Point.

MELISSA SANCHEZ: Thank you for having me.

CHAKRABARTI: This recent arrival of many Central American immigrants isn't the first wave to have come to Whitewater.

Can you tell us a little bit more about the migration history of the city?

SANCHEZ: Sure. I'd say in the late '70s, early '80s, Whitewater, like a lot of places in America, started seeing large numbers of immigrants from Mexico, people who crossed the border illegally, who were undocumented. And they settled their families in Whitewater, found jobs at the same places that a lot of the Nicaraguans did later.

And in the late '80s, with the passage of IRCA under Reagan, a lot of them did become eventually U.S. citizens.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. And so then we've seen these subsequent, over the past several years, arrival of many people from Nicaragua. Why have they come and why specifically now?

SANCHEZ: It's a complicated question.

So there's a few factors. One, Nicaraguans had been coming to the U.S. in much smaller numbers for a while, and they had plugged into the state dairy industry in Wisconsin. A lot of them were working as undocumented immigrant workers for the previous decade or so. But in 2018 in Nicaragua, the country took a turn toward authoritarianism.

There's killings of a lot of students who are protesting in the country. And after that, the economy collapsed. So in 2019, 2018, you start seeing just large numbers of people leaving, and the numbers only go up after Biden takes office in 2021.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. And then to Whitewater specifically.

SANCHEZ: Yeah. So among the first people we met who had gone to Whitewater, that would've been this man named Ariel who you referenced earlier. So he came in the spring of 2020. And what we understand is during the pandemic, a lot of factories lost workers. People who just no longer wanted to be close, in such close proximity to other workers where they could get sick. And there was a high demand just for labor.

And so people like Ariel who had been working on dairy farms in the state suddenly learned that there were job openings in places like Whitewater. Whitewater isn't the only place that saw new immigrants show up, but it's a huge number.

And so Ariel came, and his brother came, and then his wife came and then, pretty soon, all of his little community back home at Nicaragua is in a place like Whitewater, where there were tons of jobs and just this desperation from employers to hire new people.

CHAKRABARTI: You know what's interesting, Melissa, and I'm really grateful that you walked us through the long-term immigration history to Whitewater.

It helps to explain a lot of what we experienced when we went there, and I know you've been reporting there for a period of six months. And that is the stark contrast between how Whitewater has been portrayed in much of the media, when we played that tape from former President Trump before, about him saying it's overrun, the schools, like, can't function, et cetera, versus the reality, when you actually go to Whitewater. And everybody we talked to, they all said, immigration is the long part of this city's history.

It's not the immigration that anyone objects to. Chuck Mills, who we heard from a little bit earlier, he said, Hey, one of the good things about having the University of Whitewater-Wisconsin in the town is by virtue of the university, he felt that Whitewater had also been quite diverse for a long time.

So I wonder what you learned from people about that point, the reality of their lives versus how they'd been portrayed, more broadly.

CHAKRABARTI: It's complicated. So there were immigrants before in Whitewater, and there had been some sort of peace before, the Mexicans I'm referring to. But people who come here as undocumented immigrants do slip into the shadows, as they say.

So they were a quieter, though present, part of life in the community. The Nicaraguans who came are asylum seekers. So they did come with a different set of privileges and kind of this different narrative around them. And it was, as opposed to this kind of slow and steady arrival of Mexicans, it was more sudden.

But the biggest complaints that you hear from folks are that Trump and a lot of right-wing media have portrayed these new immigrants to be criminals, that there's like rampant crime, that there's cartel activity, that isn't true. So the best indicators that you can look at for violent crime or homicides, and there haven't been the most recent, one was a university student who was accused of murder.

So I think there has been this narrative that the new immigrants brought with them a lot of crime and we're not seeing it in the numbers. What we are seeing is more police stops for this issue of driving without a license. But a lot of the folks in town feel really grateful that there's more diversity in town.

They know that local employers are able to hire folks. And we haven't seen the kind of violent or cruel rhetoric that you hear outside of Whitewater, you don't hear that from anybody in town.

CHAKRABARTI: And that sort of national narrative that's been applied to Whitewater, the sense that I came away with is that it was a cause of frustration. Because it overshadowed the things that the residents and officials of Whitewater say they actually need, which is just resources to help serve everybody. Now, on that point, I do want to talk about some of the uncertainties around the number of Nicaraguans who have come into the city. The police chief says, or he had estimated, at one point, there's between 800 and 1,000 new people. Do we know what the exact number is?

SANCHEZ: I wish we did. We can't count them all and people move, and they come and go, but I think his number is not unreasonable.

The methodology might've been a little bit tricky, but we got federal court data that shows how many people have immigration cases and say that they live in Whitewater. And it's an imperfect number because it leaves out people who came and just bypassed border patrol together and are just undocumented, so they're not counted by anybody. But those numbers show around 500 or so who have settled in Whitewater.

Who really knows? You talk to people who run little convenience stores in town, and they think 1,000 plus. Other folks say 500. I'd say the chief's numbers are in the ballpark.

CHAKRABARTI: Okay. Earlier, we mentioned this letter that Chief Meyer had written. And let's talk more about that. So I'm going to play a little bit more of our conversation with him. And of course, Melissa, as having reported from Whitewater for a long period of time, in your story, you also talk about his letter in detail.

By the way, I want to say that Melissa's story, ProPublica story, is linked at our website onpointradio.org.

Now, when Whitewater Police Chief Dan Meyer told us that traffic stops involving an unlicensed driver have tripled since 2022. He also added that the department has only one bilingual officer on staff.

So what that means is that when a driver doesn't speak English or doesn't have a valid ID, processing a single stop can be time consuming. And Meyer says that means that officer isn't doing other parts of the job.

DAN MEYER: We clearly are not providing the same level of service to the overall community that we once were.

We need help. So we need resources. The city budget here can't necessarily just pay for another officer, two, three, whatever the need might be. And nobody here locally asked for this challenge.

CHAKRABARTI: Now, once again, in 2023, Meyer discussed the problem with the city's Common Council. And in December of that year, he sent letters to President Biden and a dozen other federal and state officials.

And that letter described, quote, the impact of demographic change that we are seeing in Whitewater is acute, end quote. And that letter quickly became a right-wing media talking point.

MEYER: I've been asked yeah, why didn't you assume that would happen? Yeah, to some degree we did. I was getting calls on that, before the letters actually left the building.

So the timing of it surprised me more than anything else. People ran with that very quickly.

CHAKRABARTI: City Manager John Weidl's name was also on that letter, too.

JOHN WEIDL: I had an elected body at that time that was interested in ensuring that all levels of government understood that Whitewater is having challenges.

Advertisement

Chief and I worked very hard to focus on the issues, to focus on what we thought the needs were. I would not have written that letter if it was up to me. It was a perfectly acceptable path. It's a legitimate path. It would not have been my preferred method. I think it was very noisy, and the only reason we're talking right now is because that letter was written.

CHAKRABARTI: Now the letter also states, quote, Our law enforcement staff have responded to a number of serious crimes linked to immigrants in some manner, end quote. The letter also says, quote, Each individual has a different reason for coming here. Some are fleeing from a corrupt government. Others are simply looking for a better opportunity to prosper.

Regardless of the individual situations, their arrival has put a great strain on our existing resources, end quote.

Now, Police Chief Meyer also told us that the staffing strain at the Whitewater Police Department predates the arrival of the new migrants. In 2008, the department had 24 sworn officers. 16 years later, that number has not changed.

Weidl says policing isn't the only city service that requires more resources to meet the city's current needs.

WEIDL: The school district has challenges. They've had to hire more teachers that are bilingual. I wish we had money for an immigration liaison, which our police chief has talked about. And we had, there's an appropriation in the federal budget from Senator Baldwin for that.

The city is responsible for some form of transportation, which is contracted out by third party, and some of that is reimbursed by the state. They're facing similar challenges. Not all of their dispatchers are bilingual. Not all of their drivers are bilingual.

CHAKRABARTI: As for the letter, it was largely ineffective.

The Biden administration and many state officials who received it did not offer additional help to Whitewater. However, as you just heard, Senator Tammy Baldwin is pushing for a federal appropriation to fund an immigrant liaison position for the city. And the city has also received a $375,000 grant from the Department of Justice to hire three new officers over the next three years.

MEYER: We're not getting the dollars and cents necessarily directly from the politicians, but this process, I think, has brought awareness to it.

CHAKRABARTI: As for City Manager John Weidl, he's grateful for the incoming resources, but still worries about some of the politicized fallout that came along with it.

WEIDL: Not that some of the attention hasn't been beneficial, so I'm very thankful for all of that.

Having said that, it's brought a lot of attention, negative attention. And in many ways, I think it's given legs to some negative stereotypes.

CHAKRABARTI: Melissa Sanchez with ProPublica, tell us about what you heard in Whitewater about the fallout that people feel happened because of that letter.

SANCHEZ: It's been mixed.

So there's a prominent immigrant rights activist in town who's an immigrant himself from Mexico, who said he doesn't feel welcome in the city anymore, in part because of the fallout from the letter. A lot of the advocates in town who are just incredibly frustrated with what Trump was saying, with what a lot of the Republican politicians have said.

They felt more motivated to do even more to help immigrants. One really interesting thing is that very few of the new immigrants from Nicaragua who we spoke to had any clue that this was happening. They were just too busy, living their lives and working and trying to survive.

CHAKRABARTI: That's so interesting, because we've been using this phrase resources over and over again, aka money. And the focus has so far been a lot on the police department, because Chief Meyer was so outspoken about this. But what else did you find about the kind of city services that need more resources now in order to support all residents?

SANCHEZ: The manager and the chief have talked a lot about this need for somebody like an immigrant liaison, and the school system has actually created a position that does a version of this. The person who used to have this job talked about spending hours helping people do basic things like apply for an apartment, services that could help people overcome some of these barriers that we might not have thought about it.

And I don't know if that's the city's responsibility, but it's something that the more, the city or some entity can do, that the fewer problems you might find later on.

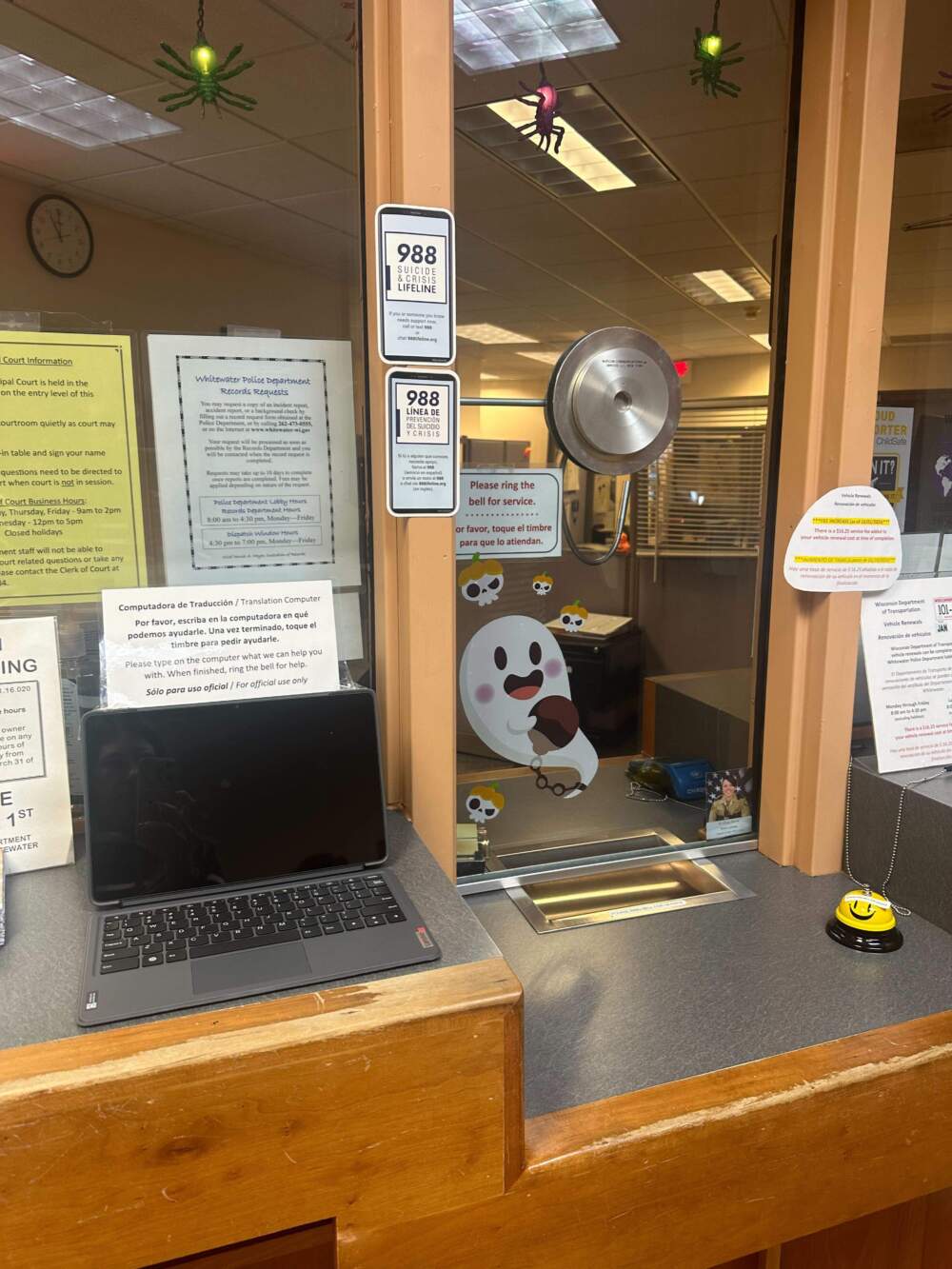

CHAKRABARTI: It's so interesting. When we were there, you can see both the big and small ways in which Whitewater is trying to cope with the lack of resources.

Because when we first walked into the police station, for example, as we waited in the waiting room, one of the things, first things that we saw was this laptop, and there was a sign. That was written in Spanish. Please type in what you need, or your request on the laptop first, in Spanish, and then knock on the window. Because the computer would translate it, translated to English and someone could help them.

Did you see things like that?

SANCHEZ: Yeah, we did. And I asked about that. And when my colleague, Maryam, I think she might have seen somebody use that. But you're also talking about people who might struggle to use a laptop. And so I know a lot of police officers use Google translate on their phones to talk to folks.

There is one, the one bilingual officer, Saul, whose family comes from that same part of Mexico that prior generation of immigrants had come from, and I did a ride along with him and I got to watch how one of his colleagues, I think it was his supervisor, had pulled somebody over who didn't speak English.

And so they call Saul for help. And Saul has to drive over across town and then help do, not just translating, but he also has cultural competency.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah, so there's other aspects of supports that not just the city, but nonprofit groups provide for residents of Whitewater, both old and new.

And so let's talk a little bit about that because Karla Ruelas. This is a bilingual legal crime victim advocate at New Beginnings, and that's a nonprofit that serves victims of violent crime in Walworth County, where Whitewater is located. And Karla says she's seen an increase in the need for her services, but not just when it comes to navigating the legal system.

Because she speaks Spanish, Karla has been helping folks navigate multiple bureaucracies like housing and education.

KARLA RUELAS: It's pretty difficult to come to a new area when you're coming back from different traditions, a different context, different backgrounds and cultural environments, there was lack of resources for the community in general.

All of us around the area work together, trying to give them those resources, our extra help to see how we were all able to pitch in and for them to be comfortable.

CHAKRABARTI: New Beginnings works with those who have experienced domestic violence and sexual assault. And requests for these resources have increased across the board in the area Karla serves, not just in the Spanish speaking communities.

But she says newly arrived immigrants have unique needs.

RUELAS: Some of the victims that do come in don't have those natural resources they can go to directly, like family or friends. So they feel alone. Most of these communities, because of their background and depending on where they're coming from, aren't comfortable going back to law enforcement or the DA office.

So it's also taking that perception of where they're coming from and letting them know, hey, our communities here are different.

CHAKRABARTI: New Beginnings does their best to help everyone who contacts them. They guarantee bilingual services during their office hours. They offer a 24-hour hotline, but Karla says resources sometimes still feel tight, and she says organizations like hers just weren't ready for the increase in need.

RUELAS: We were not prepared in general, and we made it work from there. Unfortunately, because of funding, sometimes we're unable to provide those services, but we try to accommodate as much as we can, to actually give them the resources that they require in that moment. We do need more resources with funding, but we also kind of make it work at the end.

CHAKRABARTI: So that's Karla Ruelas, a bilingual legal crime victim and advocate at New Beginnings. Melissa, hang on here for just a second, because we have to take a quick break. And when we come back, I want to learn from you what you heard from residents of Whitewater about what the near future may hold for the city.

Part III

CHAKRABARTI: You're back with On Point, I'm Meghna Chakrabarti, and this is the latest episode in our special collaboration with ProPublica, and ProPublica's Melissa Sanchez joins us today because we're hearing about Whitewater, Wisconsin, and what a community needs to serve all of its people, longtime residents, and an influx of newly arrived immigrants.

La Tienda Mexicana San Jose is on Whitewater's Main Street. Just about everything is for sale here.

On the front window, in Spanish and English, are signs for meats, vegetables, household goods, and Western Union wire transfer services.

Owner Juana Barajas stands behind the counter. A basket of fresh eggs is to her right.

Wall high shelves behind her, packed with over-the-counter medications.

Juana has also added novelty Nicaraguan flags and toy boxing gloves printed with Nicaragua, boldly in blue.

JUANA BARAJAs: There were, before '19, 2019, that was all Mexicans, and now that's why you realize we change everything, because from the other, the immigrants from other countries, Nicaragua, most of them, they're like, the Nicaragua.

CHAKRABARTI: So are there more customers now than before?

BARAJAS: Yeah, 100% more.

CHAKRABARTI: Juana has lived in Whitewater for more than 30 years, and she's been with the store for more than 20.

She's originally from Mexico, and remembers how much she missed the flavors of home when she first moved to the U.S. She sees that same longing in Whitewater's new migrants, so she stocks as many Nicaraguan products as she can.

BARAJAS: Actually, I think I've been helping a lot, in the products, I try to buy everything that they need. Either tell me, you know what? Buy this, buy that. I try hard. Believe me, I try hard.

CHAKRABARTI: Juana's husband is Nicaraguan, so she jokes that some of the flavors aren't quite to her Mexican palates' liking.

BARAJAS [TAPE]: I start liking that. But the thing that I don't like, that they don't use, salsas. Yeah. They're team ketchup, and then I'm team salsa.

CHAKRABARTI [TAPE]: They're on team ketchup?

BARAJAS [TAPE]: Yeah, they're team ketchup.

SCHEIMER [TAPE]: It's a difficult divide to overcome.

BARAJAS [TAPE]: Yes, Just imagine how I'm suffering.

CHAKRABARTI: (LAUGHS)

CHAKRABARTI: The narrow aisles are stacked with products from across Latin America, colorful boxes and bottles. Sometimes hurriedly placed on the shelves as if Juana never has enough time to fully unpack her wares.

As we talk, a young man steps out from one of the aisles and waits behind us at the counter. He wants to buy a phone card to call Nicaragua.

He pays with cash, a $100 bill.

The young man smiles. Thanks Juana, and leaves. Juana watches him go and says these days she's seeing many newly arrived Nicaraguans struggling to find housing in Whitewater, and she believes it's because of low vacancies and much higher --

BARAJAS: Rents that went up, like crazy. There's a lot of opportunity made, there may be in the other states they don't have. And this way, they're coming here too. But guess what? They have the job. They have the money. But they don't have a place to stay.

CHAKRABARTI: Juana says some people can't afford to stay at all.

BARAJAS [TAPE]: And there's a lot of people leaving to another town or definitely leaving to their countries. Yeah.

CHAKRABARTI [TAPE]: That's happened to people?

BARAJAS [TAPE]: like a lot. Like a lot. Yeah, they're not like Mexicans. We've been here. We're going to stay here. We're going to die here no matter what. But they're like no. We're not going to suffer this. Hell no.

CHAKRABARTI: But for now, the customers keep coming to La Tienda Mexicana San Jose.

There's already another person waiting at the counter.

CHAKRABARTI: Gracias. Adios.

BARAJAS: Hasta luego, chicas.

CHAKRABARTI: It's Juana Barajas in Whitewater, Wisconsin. Now, Melissa, I'm wondering if you could pick up on what Juana said there at the end, that, you know, it's 2024, not 2020, so it's been roughly four years, and she says now that actually housing availability and unaffordability are a problem for new immigrants or migrants.

SANCHEZ: I think that's partially true. So a lot of the housing stock that once served university students has flipped and it has, it's now mostly immigrants from Nicaragua. Maryam spoke with one landlord in town who told her that, he saw his tenants switch from students to immigrants and he's able to charge them more in rent. In part, because they pack more people to an apartment, whereas you might have a couple of students before, you might have five or six or seven people.

So we have heard from some immigrants that rent is expensive, but there's more to it than that. A lot of times folks can't afford to put down a security deposit and last month rent, like you often have to. I do think the bigger issue that's happening that we've witnessed over the past few months is that some of the jobs that used to be there have dried up.

SANCHEZ: I don't know if the market is saturated, if there's too many workers now and not enough jobs. We have heard that some of the factories that are more prominent in town have done some layoffs. So even Ariel didn't have a job for a few months when we first met him, and he had to go find a job in another suburb.

But we have talked to people who have left Whitewater because of housing costs, and we have heard from Juana and from her employee ... that there are folks who are leaving the city altogether or leaving for back home. And again, that might be because of housing, that might be because of jobs, and that might be because they saved up the money they wanted to save up, and now they can go home and open their business that they dreamed of opening.

CHAKRABARTI: Yeah. And that's why I think your reporting and our experience there is so important, because it's never just any one thing, right? And this issue of immigration and migration so frequently in the national media, national politics gets flattened down to one thing. In terms of the benefit that the new arrivals or the Nicaraguan community in particular have brought to Whitewater, you mentioned one very important one. They have been a source of labor for surrounding companies that want it and need it.

What kind of economic impact do you think that the Nicaraguans have had on the city?

SANCHEZ: I think it's pretty significant. I think Juana is the one who told me that before the Nicaraguans came, she said that the Mexican immigrant community might send home five or $6,000 remittances every weekend.

And now that number is up to $100 or $120,000 in a weekend. So that kind of shows how much money we're talking about. But that's money that's leaving Whitewater. And one of the complaints you hear from the right is that immigrants come and they work, but their money isn't staying in town.

And there's some truth to that. Ariel talks about how he can maybe spend half of his money, and send the rest back home. So I think it's complicated, but there have been, there is a new store that opened up that's serving these folks. A lot of the people we talked to said that they feel like the city is thriving more. Because you see more people walking around. Some of the businesses are not boarded up anymore. It's a hard thing to measure.

CHAKRABARTI: I was so delighted to meet Juana, because she's just a lovely person. And you heard her joke there about team ketchup versus team salsa. And she's married to a Nicaraguan, but that also brought to mind, and she's not representative of this, but that brought to mind that in your story, you mentioned that there are perhaps some tensions between the new Nicaraguan residents of Whitewater and that longstanding Mexican American community. Can you talk about that?

SANCHEZ: Yeah, I'm so glad you brought that up. It's something we noted and were really struck by. I spent one afternoon a few months ago in a trailer park where a lot of immigrants live, Mexicans and Nicaraguans.

And I was talking to two undocumented Mexican women who have been living in Whitewater for more than 30 years and they're undocumented. And their children are U.S. citizens, because they were born here. And they are incredibly resentful and angry that all of these newcomers from Nicaragua, immigrants who look like them, who speak like them, they have access to government privileges that they will never have as undocumented immigrants.

They can access work permits, which undocumented immigrants cannot, and if they can pass the test, they can get driver's licenses. One of the women told me her kids are voting for Trump, because they're so angry that Biden has let all of these people in and given them something that they cannot have.

They're frustrated with the failures of the Democratic Party to enact any kind of immigration reform.

CHAKRABARTI: Can you tell me more about why you think that's important, an important part of this story?

SANCHEZ: You're going to have U.S. born citizens whose parents are undocumented who are voting for Trump in a swing state.

I think that's important. It's not just Whitewater. I've heard this within my own family, with my friends who come from Latino families. I was at a party the other day, just my own personal life, a Peruvian immigrant brought up this issue of all of these new immigrants are coming, like they're all being let in and it's not like how we had to do it.

So I think that's been missed a little bit by the media. We say a lot about how immigrants or Latinos aren't a monolith. And the fact is the Nicaraguan immigrants, just like the Venezuelan immigrants who have come in the past few years, they're coming through the asylum system. They have status.

They're not undocumented. They can get driver's licenses in some states, and that makes people feel really left out. The folks who have been here for 30 or 40 years, who are still undocumented, they want to access those same things. And the people in their lives who can vote might be voting for Republicans because of this.

So this brings me back to thinking about what Chuck Mills said earlier. We heard him say that he's supportive of the immigrant community in Whitewater, but he's still voting for Trump. And his reasons were he doesn't believe that another Trump administration would enact a mass deportation program. Because according to Mills, the first time around there was no targeting of immigrants beyond, in Chuck's view, MS-13, etc.

Now, obviously, that's not true. There's just so many examples of the Trump administration's immigration policy which fly in the face of that. But the reason why I'm thinking about that is that the frustration that you were describing, that the children of the Mexican immigrants were feeling, leading them to possibly vote for Trump.

That outcome could lead to a real disturbance, a profound disturbance in their very community. And it's just something that, it's a little, it's a cognitive dissonance that I can't quite resolve in my own mind.

SANCHEZ: No it's really hard. Their parents could be deported with a Trump administration, because their parents are still undocumented, but they will vote for him.

And I've heard over and over from Chuck and a lot of people like Chuck, that they don't think Trump is actually going to say what he says he's going to say. And we don't know what's going to happen. I think it would logistically be very difficult to do the thing that he says he wants to do, but it's clearly winning over voters.

CHAKRABARTI: I wonder, since you also talk to Chuck a lot, and I wonder what you think of this, because he was a delightful gentleman to meet also. But when he said, MS-13, et cetera, et cetera, in virtually the same breath, where he also was so grateful for the Nicaraguan families who live on his street now, because he enjoys having them around much more than he enjoyed having college students on his street.

I started thinking, and this is also part of this the bigger immigration story across the country, that Whitewater is emblematic of. Chuck knows the families who live next door to him now, so they are part of his community. But his objection to migration in the United States now seems to have to do with this abstracted problem somewhere else, right?

It's not the new Whitewater residents that are the issue in his mind. It's MS-13 somewhere else. In your reporting about immigration overall with ProPublica, have you found that there's that kind of, what's happening near me is okay, because I understand it, but the problem is somewhere else?

SANCHEZ: Yes, but I think, like we shouldn't dismiss this idea, even though you can say my neighbors are fine, but there's the immigration system is broken. Both things are true and can be true. Chuck, like all of these people have seen these huge numbers of people come in.

And the U.S. can't actually vet everybody who comes in. A lot of the, like, when we don't have diplomatic relationships with countries like Venezuela, we cannot do the same kind of like criminal background checks that we can do with countries that we do have good relationships with. So they're not wrong in some of what they're saying.

And I think like you could love the immigrant next door, but wish that the government did a better job of organizing the immigration system. I don't think there's that big of a disconnect. And I think that's what Chuck's trying to say. Like he's not a hypocrite for liking his neighbors but being mad, at the border is out of control or however they want to describe it.

I do think that the United States hasn't really been able to figure out what to do about our immigration system. And meanwhile, you have the real hypocrisy, is that you have businesses that depend entirely on the labor of immigrants, undocumented or not, asylum seekers or whatever. And then there hasn't been like a viable way to get these businesses to hire legal immigrants and maybe it's to their benefit, because they can underpay people.

They can exploit people, but those are hard questions.

CHAKRABARTI: Melissa, you have landed on something which is so important here, and it's the question that I came away with from our visit to Whitewater. And that is police chief Meyer decided to write to state and federal officials saying, look, we have no control over border policy in this country, but as a result of that policy, we have a lot of new migrants or new residents that we need to serve as well.

We need resource help. I'm wondering who actually, or what groups should or do hold the responsibility for supporting a city when there's so much rapid demographic change? Did you find any evidence that Whitewater had turned to those very employers that you're talking about and said, somehow you guys need to help us out too? I don't know.

SANCHEZ: Yeah, they tried. Chief Meyer showed me his notes from all of these different meetings he had with folks throughout 2022. Anybody in town who would listen to him, and they did try to reach out to the employers. They knew who was hiring these folks. To see, can you guys help us with a ride share program or something?

So we stop pulling people over for driving without a license. And they got silenced. Like we got silence. We reached out to every employer we knew of and nobody wanted to talk to us. It's not very convenient. Yeah, maybe employers have, they're clearly benefiting from what's happening.

Do they have some responsibility? Landlords are benefiting from what's happening. Do they have some responsibility? I think when you ask an immigrant this question, they don't come with the expectation that the government's going to give them handouts, like they're grateful when they get something, but they support each other.

This is why you have one family that will take in another and another, to give them a roof over their head when they first come into the city. So there's a lot of, I think, help from within the community that we can't see from the outside, nonprofits, like the civic spirit in Whitewater was just astounding.

The churches do a lot, too. Whose responsibility is it? I think it's all of ours. I don't really have a much better answer than that. And in Whitewater, you see everybody stepping up, from the police chief, to staff, to the community groups, to the university employees, to the immigrants themselves.

Voiceover provided by Jesús Marrero Suárez, WBUR's Investigations Fellow. Melissa Sanchez of ProPublica provided translation services.

This program aired on November 5, 2024.