What's Changed? 'Not Enough': Local Protesters Reflect On The Year Since George Floyd’s Killing

Tanoah Pierre didn't tell her family when she headed out to join demonstrators in downtown Boston late last May. She knew her relatives would be concerned about the coronavirus or the possibility that violence might break out and try to discourage her from going.

But with the video of a Minneapolis police officer kneeling on George Floyd’s neck already sparking massive protests in cities around the country, talking with friends and posting on social media felt insufficient.

“I need to be out there,” she recalled telling herself, “even if it’s just walk out there, and, I don’t know, scream or yell or just repeat what everybody else is saying.”

There was an element of fear, said Pierre, 19, about marching and chanting among thousands of others. And yet, "It just felt so necessary that I couldn't even think about being scared or being in danger," she said. "I just felt like this is what has to be done. And whatever happens, it happened for a good reason."

Pierre became one of thousands of people across Greater Boston who took to the streets in protest after the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and many others. Together, these protesters made political and cultural waves, igniting new conversations about racism and police brutality in Massachusetts and around the country.

To mark the one-year anniversary of Floyd’s murder at the hands of police, WBUR asked some of the people who protested in Boston last summer to reflect on their experiences — how they've changed, how their communities have changed, and where they hope the movement for racial justice will go next.

A Process Of Learning And Unlearning

One reason Pierre wanted to protest was to send a message to politicians.

"If you apply enough pressure, then they start to respond," she said. And last summer's protests did help propel police reform measures at the state and city level.

And yet, she added, racism can't be dismantled by changing only the law. People have to want to change their minds — their knowledge gaps, biases and prejudices. "A lot of people," she said, "aren't willing to do that."

For Pierre, the protests of last summer helped catalyze a process of learning and unlearning. Growing up in Haiti, she was aware of racism in theory, she said, "but you don't really experience racism in a country that's 95% Black."

That started to change after she moved to Massachusetts to attend UMass Amherst.

On top of health and science classes, the aspiring neurosurgeon added a concentration in Global Black Studies. She's learned more about systemic racism, she said, and become more conscious of the double-standards that a white-dominant society often places on Black women. In some cases, that has meant "unlearning" certain behaviors — speaking softly, suppressing her accent, avoiding certain kinds of fashions — which she feels she may have unconsciously adopted to make herself more accepted by her white peers.

"Speaking a certain way or walking a certain way ... is not going to suddenly make them think you're human," Pierre said. "And even if it would, you shouldn't have to prove your humanity to some people."

'We Win The Day We Start To Fight'

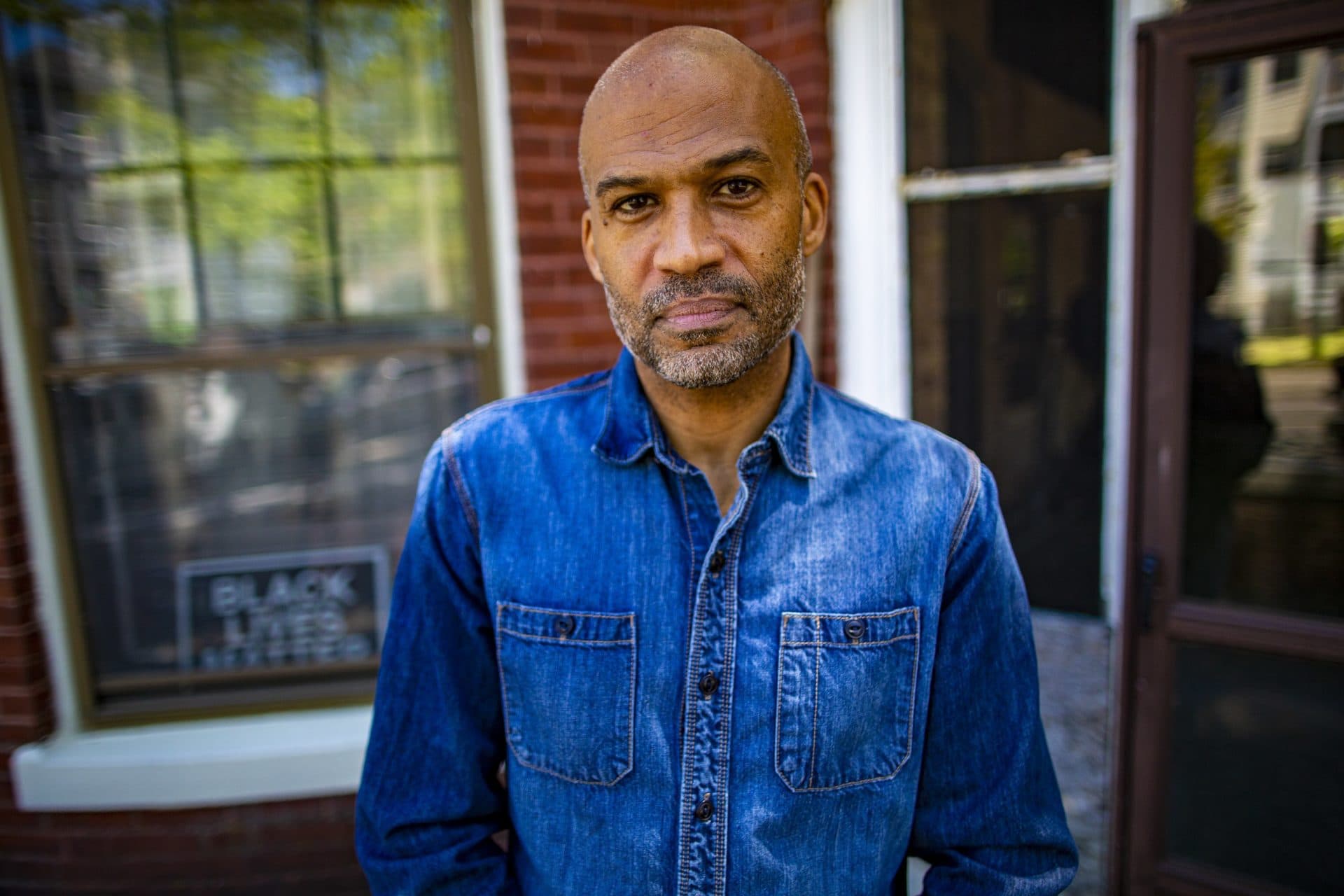

As a lawyer who specializes in working with advocacy groups, Carl Williams figures he has attended hundreds of protests — advising people about their rights, monitoring police conduct and counseling those who get detained or arrested. Because of that, he's used to seeing the same faces at protests, rallies and other events.

But on May 31, 2020, as people gathered near a police station in Nubian Square for a march to the State House, he looked around and realized, "I don't know a single person."

As the crowd blossomed into the thousands, its diversity and sheer size was "heartwarming," said Williams, who lives in Roxbury.

"I remember seeing this very young girl, probably like 8, on a little bike. She had a sign that she clearly made herself, and she was very, very proud," he said. "I was choked up."

That feeling didn't last into the night. As the official march ended and many protesters began to head home, dozens of witnesses said there was a sharp rise in police flanking the area. During a chaotic few hours, police used batons, tear gas and pepper spray to disperse the crowd. Some protesters shattered shop windows and stole merchandise.

The destruction of property was unfortunate, Williams said. However, "if we're focused on [how] someone stole a tie clip, a tie, broke a window, even burned a vehicle, and we're not focused on the largest movement for civil rights in the history of the United States, I question how much you care about human life in this country."

Like many of the advocates he works with, Williams, who is 52, regards the criminal justice system as flawed because it has so often been stacked against Black people and other historically marginalized groups. Therefore, he argues, it must be abolished to make way for alternatives that "strengthen society, not punish or torture it."

It's a politically taboo idea, he said, but at least now people are talking about it.

"We don't win the day that we get all the things that we're demanding," Williams said. "We win the day we start to fight."

To keep up the fight, Williams said he will continue his work as a lawyer — supporting those advocating for the rights of Black, brown, poor and queer people — and mentoring law students who are interested in doing the same.

Not Her First Protest, And Not The Last

"I've been going to protests since I was a kid," said Shanakawa Pereira, who was among the thousands drawn to Franklin Park on June 2 last year to take part in a rally against police violence. It wasn't a surprise to her when agonizing killings of Black people, combined with the growing anguish of the pandemic, produced a public outcry.

"It's like a soda bottle," she told WBUR at the time. "If you shake it too much, it's going to explode."

About 10 months later, as the murder trial of Derek Chauvin played out for hours on live television, Pereira, 45, tried to avoid watching it, except in short news clips.

"To tell you the truth, it made me a little anxious," said Pereira, a longtime Mattapan resident who works as a paraprofessional in a Boston public school. "With the history of us seeing trials like this, it usually ends up in disappointment."

This time, the jury convicted the former Minneapolis police officer of all charges, including Floyd's murder, a result Pereira described as "bittersweet." That's because in the days leading up to and following the verdict, other incidents of police shooting and killing people of color punctuated national headlines: Adam Toledo, 13, of Chicago; Daunte Wright, 20, of Minnesota; Ma'Khia Bryant, 16, of Columbus, Ohio; and Andrew Brown Jr., 42, of North Carolina.

"It's exhausting as a Black woman to think on a daily basis: 'Could this happen to my child? Could this happen to my husband?'" said Pereira. The Chauvin-verdict aside, that "eternal" sense of worry is still with her. "A year later, I don't think that's changed," she said.

Her fears, especially as a mother of two daughters, weigh on her, and have led her to conclude she is "definitely for defunding the police." Although she does not feel the police department should be completely shut down, she said some of the money that funds policing could be redirected toward social programs that meet neighborhood needs. Her question: "How can you police a community if you have no investment in [it]?"

She's hopeful that will change, even if she has to march in the streets for it. Last summer's protests were not her first, she said, "and it doesn't look like they'll be my last."

'It’s Not Easy To Tell A 7-Year-Old The Police May Kill Your Father'

Franklin Peralta, 43, and his wife did not show the video of a police officer pressing his knee into George Floyd's neck to their young daughters. But they explained it. They explained how police officers killed Floyd, and how Black people have long been subjected to unfair treatment by police because of their skin color.

Beyond talking about it, Peralta, a resident of Jamaica Plain, felt "we needed to get into the streets." At first, his daughters, cooped up for more than two months because of the growing pandemic, were nervous about attending a large gathering. But Peralta felt that it was important for them to participate in the protests, for reasons that were personal as well as political.

"It happened to George Floyd. But your father is a Latino man in Boston," he recalled telling them. "It could happen to [me], too. When you say something like that, they are like, 'Let's go.' "

At the time, Peralta, who works for a nonprofit called English for New Bostonians, was encouraged by the large turnout he saw at multiple protests he attended last summer. However, a year and many protests later, he still feels that "the best interaction I can have with police is none."

"When I'm driving along with my kids in the back, I'm very, very concerned, because if the police stop me," he said, "my kids are going to panic. It's not easy to tell a 7-year-old the police may kill your father."

Research has shown Black and Latino men are significantly more likely to be killed by police than white men. For Peralta, the statistics reveal a society that holds "this belief that, because of who we are, we are a threat."

"That must change," he said, "so my kids, and the kids of my kids, don't have to go through these type of conversations."

Having Uncomfortable Conversations

Prior to the summer of 2020, Emily Conklin had always thought of herself as a "good liberal."

"I thought I thought all the right things, and I would work for the right things, but I wasn't actually being very active or supportive in my community," said Conklin, who works for the nonprofit Clean Ocean Access.

That began to change after Floyd was murdered, when she and her roommates saw protests bubbling up in Boston. "I've always been in a safe place, and my body has never really been on the line," she said. "And so in this situation, it no longer felt acceptable for me to sit in my safety."

On the evening of May 31, Conklin said she and her roommate made their way down from Somerville, crossed the bridge near MIT, and stood by the State House. As they watched a mass of people march up the Boston Common, "I just remember feeling like this is the most important thing we could be doing right now."

In the months that followed, Conklin, 29, underwent a shift politically and personally. She started attending Somerville City Council meetings and joined a group that helped push the city to make cuts to its police budget.

In her personal life, Conklin said she has become more willing to engage family and friends, who are mostly white, in potentially uncomfortable conversations about race and racism. Asked whether she's witnessed a change people's attitudes this past year, she said, "Not enough."

"I'm very much someone who has always tried to make people happy," she said. "And I think that in these issues of social justice ... it's very easy to make people uncomfortable or unhappy. And I just don't have room for that anymore."

This segment aired on May 25, 2021.